Each of the 18 women whose stories unfold in this unique work made heroic, profession-changing contributions to journalism.

Covering nearly 300 years, Schilpp and Murphy have elevated these women either from the obscurity of historical footnotes (Elizabeth Timothy, 1700—1757) or from the frozen stuff of legend (Nellie Bly, Anne Newport Royall, Margaret Fuller); they have made their subjects working journalists whose careers and accomplishments were indeed heroic and inspiring, but human.

Aside from Timothy, Royall, Fuller, and Elizabeth Cochrane Seaman (Nellie Bly), the authors have included Mary Katherine Goddard, colonial publisher; Sarah Josepha Hale, first women’s magazine editor; Cornelia Walter, editor of the Boston Transcript; and Jane Grey Swisshelm, abolitionist, feminist, and journalist. Others include Jane Cunningham Croly (“Jennie June”); Eliza Nicholson (Pearl Rivers), publisher of the Picayune; Ida Minerva Tarbell, muckraker; Elizabeth Meriwether Gilmer (Dorothy Dix); Ida B. Wells-Barnett, crusader; Winifred Black Bonfils (Annie Laurie), reformer; Rheta Child Dorr, freedom fighter; Dorothy Thompson, political columnist; Margaret Bourke-White, early photojournalist; and Marguerite Higgins, war correspondent.

Great Women of the Press. Madelon Goldent Schilpp and Sharon M. Murphy. Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press, 1983

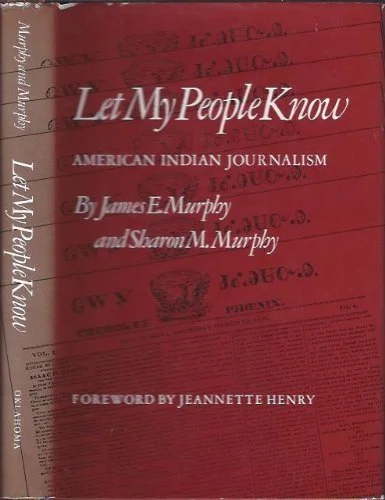

This is a useful compilation of media instruments that Native Americans have used since Cherokee Phoertix appeared at New Echota in 1828. Often misrepresented or ignored by non-Indian journalists, Indian spokesmen and women have expressed their viewpoints in tribal, inter-tribal, regional, and organizational newspapers; special periodicals; missionary society and boarding school newsletters; and in recent years radio and television programs on tribal stations or air time purchased from white broadcasters. Their freedom of expression has often been compromised by censorship from tribal governments, biases imposed by Christian missionaries, ignorance among nonIndians hired to produce Indian publications, paucity of training given Indian news personnel, and shortage of funds. Indian authors and broadcasters have enjoyed theoretical protection by the First Amendment to the Constitution of the United States, nevertheless, buttressed by the federal Indian Bill of Rights (1968). With this encouragement, "Indian media" have evolved as testimony to "the unconquered will of Indian peoples," the authors conclude, and at present constitute "a young giant just awakening" (p. 161).

Let My People Know: American Indian Journalism 1828 - 1978. James E. Murphy and Sharon M. Murphy. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1981

Other voices: Black, Chicano and American Indian press

Publisher : Pflaum/Standard (January 1, 1974)

Language : English

Unknown Binding : 132 pages

ISBN-10 : 0827800142

ISBN-13 : 978-0827800144